Hello! My name is Emma Baker and I am an undergraduate student at George Fox University studying Psychology and Christian Ministry, and the first intern for Blueprint 1543. I am currently the Chapel Director for the School of Theology at George Fox University and I have been leading worship for 7 years. I’m going to be highlighting some great books for our blog, and you’ll probably notice that I have a special passion for trauma-informed ministry. It’s my hope that whether you are a pastor, youth leader, volunteer, counselor, parent or teacher, my book reviews and practical suggestions will show how psychology can be useful for ministry, and help make the spaces you inhabit safer for those affected by trauma and promote human thriving.

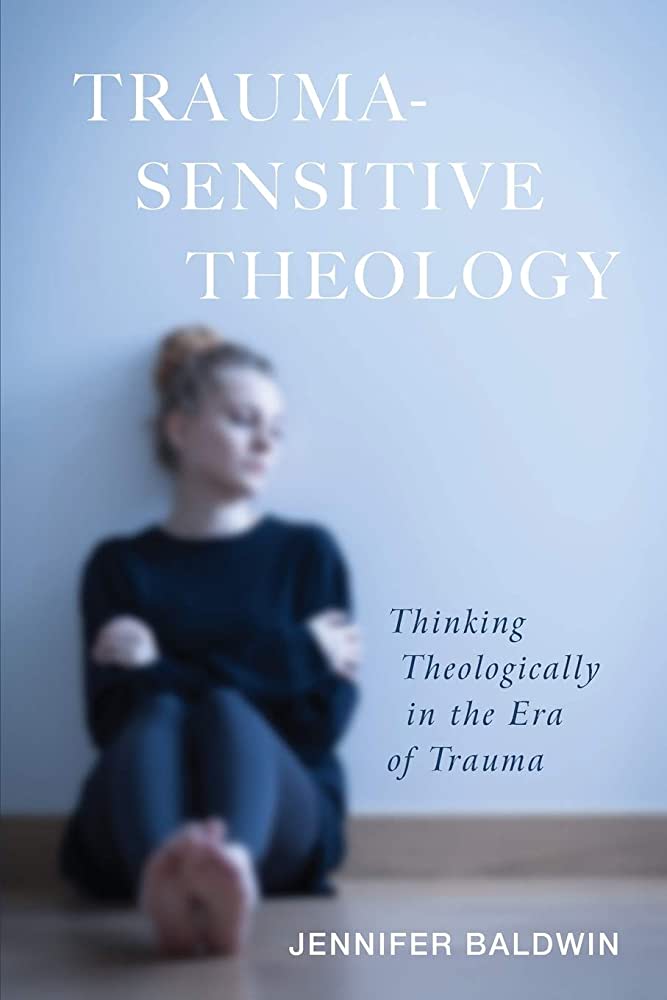

Trauma Sensitive Theology by Jennifer Baldwin

In Trauma-Sensitive Theology: Thinking Theologically in the Era of Trauma, Baldwin gives a powerful call to consider trauma as a relational wound. This makes the relational healing present at the center of the Gospel vital and increasingly relevant for modern churches. Paying close attention to those in the margins, as Jesus calls us to in the Sermon on the Mount, will always be the way to the heart of God and the sign that the Kingdom is breaking in. Envisioning Jesus as a survivor of trauma with radical solidarity and sympathy for those who have experienced trauma gives us a way forward.

What is Trauma Sensitive Theology?

Trauma-sensitive/informed theology is a relatively new branch of constructive theology. The hope is to incorporate psychological science into the way that we understand the incarnate Jesus and God’s plan for reconciling the world. Part of that means considering the experience of the trauma-survivor into how we understand theological practices and doctrines.

Why is trauma-informed theology necessary?

People in our congregations have or will experience trauma within their lifetime. Jesus was a “man of sorrows” who endured great trauma. Misunderstanding that element means missing a bit of the fullness of who Jesus was. The psychological study of trauma can offer insight on this aspect of Jesus’ lived experience. Additionally, trauma victims in churches who do not hear trauma-informed theology often develop a sense of shame and isolation. This leads to persons who experience trauma leaving congregations or not feeling able to live authentically within their communities.

What is the purpose of trauma-informed theology?

There are many possible positive outcomes to exploring this type of theology. At minimum, it recognizes the complex and often coexisting physiological, phenomenological, spiritual, social, and emotional effects of trauma, and offers a theory of how God relates to trauma survivors. This is transformative for communities and individuals affected by trauma, because it gives a nuanced way of relating to God that places Jesus in solidarity with survivors. Trauma-informed theology moves away from operationalizing trauma and making traumatic experiences something that God desires as part of “the plan.” It also denies the idea that God causes suffering in order to bring forth good, which can have incredibly harmful implications for survivors.

Ecclesial and Relational Implications

Because traumatic wounds are relational, the church is in a unique position to offer a space for individuals to experience healing. It’s important to communicate that this is not because something is wrong with them, but because something wrong happened to them. Taking notes from disability theology, we can create trauma-informed and accessible spaces to foster relationships and worship experiences that affirm the image of God in those who have been affected by traumatic wounding. This requires theological and practical adjustments to the way that we discuss sin, and the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Trauma-Informed Soteriology

Baldwin then turns her attention to a specific area of Christian theology that she believes is necessary to address in order to serve congregants well. Soteriology is the area of theology that outlines doctrines regarding salvation. This includes conversations around theories of atonement, which are ways to explain how exactly Christ’s work brings salvation.

How does a theology of trauma change how we look at the Cross of Jesus?

“Theologies that valorize the traumatization and execution of Jesus as the essential feature of salvation and the divine revelation either intentionally or unintentionally, promote the enduring of abusive suffering as the marks of a pious Christian life and are dangerous.”

The implications of penal substitutionary atonement, where God’s wrath is satisfied by the violent suffering of Jesus is called into question by trauma-informed theology. Understanding how victims of violence might understand and experience messaging about Jesus’ crucifixion is a key aspect of a trauma-informed approach.

Put Into Practice

Akin to the principles of disability theology, trauma-informed theology requires us to participate in Jesus’ vision of shalom, which places inclusivity and accessibility as central commands. More awareness and small adjustments make a big difference. For example, “Lay your burdens down at the door” may guilt people who experience traumatic wounds if they continue to experience the physiological, social, and emotional effects of their experiences. A trauma-informed reframing communicates that Jesus is present even in the midst of pain, and that worship is not conditional on feelings. Likewise, illustrations with vivid description of Roman torture methods may retraumatize those who are ever-aware of visceral and graphic violence; it’s so important to consider ways to decentralize death and violence, and convey that it is not the main source of meaning-making in the Christian story.

Other practical considerations: Being aware of sudden sounds, flashing lights, or the volume of the worship music is something to be sensitive to. Instructions to shout or do some sudden movement may make the environment feel unsafe. The most important element of being trauma informed is the ability to make space for the stories and lived experiences of the people in your context. Creating neutral environments that allow people to opt out of certain experiences can provide the posture of humility that demonstrates hospitality towards those who are healing from trauma. Making a lobby space or easily accessible quiet room available with water, snacks, dim lighting etc., so that people can take a break if they feel overwhelmed in an environment is helpful. Knowing community mental health resources and explicitly endorsing them from the pulpit does not diminish the power of the gospel or the church community to transform in people’s lives. Pastors and congregants alike show up in hospital rooms with an understanding that nurses and doctors are a necessary part of a person’s healing, but they are not the whole.

Conclusion

In the second chapter of the Gospel of Mark, there is a crowd surrounding Jesus, a group of friends lower a paralytic man through a hole in the roof. Their faith and humility demonstrated that they could not save or “fix” their friend but they could remove the practical barriers between their friend and Jesus. We must have the same willingness to make a way for those among us who have experienced trauma to encounter Jesus. Churches must have the humility to recognize that there may be barriers for others that are not immediately obvious when it comes to liturgical design and worship spaces. Things that we say may communicate unwanted theological messages to members affected by trauma and place unnecessary burdens on those living with the effects of trauma. The goal of accessibility is not conformity but a community that desires to encounter Christ in and among one another.